Published

- 6 min read

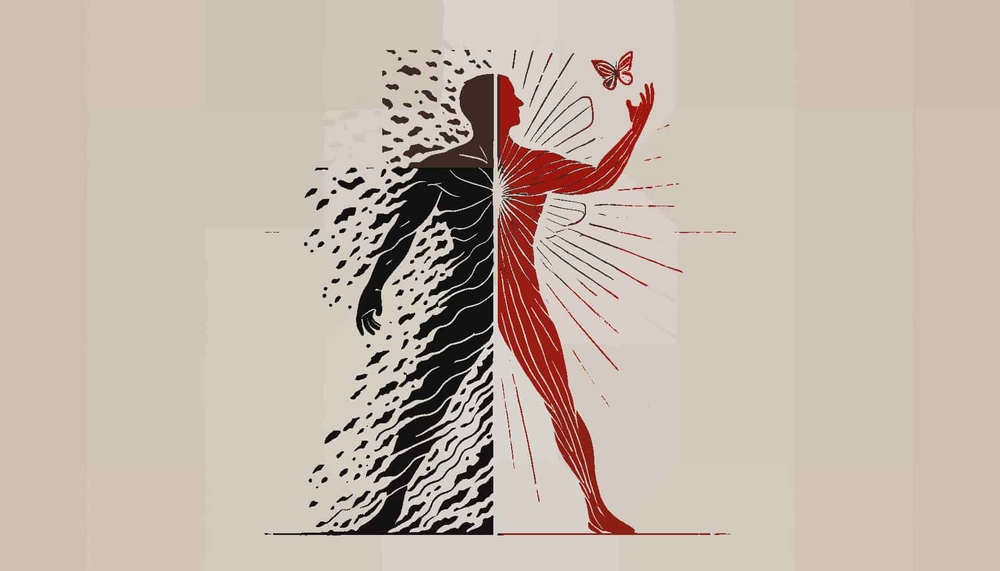

Re-frame Pain to Reduce Suffering

Re-frame Pain to Reduce Suffering

A lot of suffering doesn’t come from the pain itself, but from what I call meta-pain—the complex psychological suffering that emerges when we try to process a simpler pain. For example, after losing three days of work to hard drive corruption, I’ll experience frustration and anger. That’s unpleasant enough, but if I start framing it as a sign of life’s futility—Why do I even try if it’s all going to waste?—I turn that basic frustration into full-blown suffering.

But if I frame it differently—as an unfortunate incident and a reminder to back up more frequently—the pain stays contained. How we frame pain determines the depth and duration of our suffering.

Why Does Pain Exist?

The big existential question: why does pain exist at all?

Philosophers and theologians have been wrestling with this for centuries, trying to reconcile the abundance of pain with our expectation of a benevolent universe. But maybe that’s the whole point of pain—we don’t like it. Since we don’t like it, we avoid it, fear it, and try to eliminate it. This in turn helps our survival. Pain is a natural signaling mechanism, a necessary part of life.

But calling it “natural” isn’t the same as calling it “good.” Pain isn’t always functional (think of disease or chronic pain) or evenly distributed, but it generally serves its purpose. Most of the time, pain is a signal that something about our state, behavior, or environment needs adjustment. It gives us a reason to act.

In some cases, like with people who can’t feel physical pain, we see how essential it is. Those individuals often struggle with danger avoidance and self-care because they lack this critical feedback mechanism.

Why Do We Suffer?

We don’t suffer at all pains—just the ones we can’t understand. For example, the crying of an infant, the pinch of a needle, or the soreness of exercise doesn’t usually cause deep suffering. It’s annoying, sure, but we tolerate it because we understand it’s necessary. I call these necessary pains.

When pain fits into a functional framework, most adults don’t dwell on it or suffer meta-pains as a result.

But there’s another kind of pain—what we often consider superfluous pain—like chronic illness or the emotional weight of depression. These are the pains that trigger anger, pessimism, and extended suffering. We suffer most when we can’t find a reason behind the pain.

It’s like how children get consumed by the immediate sting of hurt, losing sight of the larger context. We fall into the same trap with our adult pains.

Cognitive Re-appraisal: A Way to Minimize Suffering

This is where cognitive re-appraisal comes in. We have the ability to change the emotional impact of situations by reinterpreting the context around the pain. I’ve personally used this strategy to deal with social and racial trauma. By re-framing the context, I was able to lessen its emotional sting.

A Personal Example: Dealing with Racist Incidents

As a Black man in hyper-racialized America, I’ve experienced the pain of casual racism. My life is peppered with incidents—explicit slurs, denials of service, threats of violence, and more subtle stereotyping. Each time, the initial emotional hit was painful, and some encounters left lasting scars. These scars led to hyper-vigilance and emotional over-guarding in social situations.

By my twenties, I had been conditioned to view most forms of mistreatment as racially motivated. This automatic response was a distortion; often, the real cause was unrelated to race—maybe the other person was in a bad mood, low on blood sugar, or just generally unpleasant. But the mere possibility of racial bias created what I call “anticipatory suffering.”

For example, being followed in a convenience store or sensing subtle apprehension in strangers left a cognitive overhead. It felt like I had to constantly deconstruct their projections just to assert my individuality. Over time, this led to a kind of grey emotional tint in how I viewed strangers.

Fundamentally, any form of group-based identification reduces a person’s individuality. As an immigrant, I’m more sensitive to the tension between group membership and individual personality. I joke that I didn’t know I was “Black” until I moved to the U.S., where I had to fit neatly into America’s racial taxonomy.

Re-appraising the Pain of Racism

The first step for me was accepting that I may be treated differently because of my race. There’s a segment of the population—though a minority—that will be prejudiced or unconsciously discriminatory. Accepting this fact helped me let go of the notion that it was my responsibility to prevent or avoid these situations. It wasn’t personal—it was a remnant of human psychology that “happens” to affect me.

This realization defused much of the righteous indignation or misanthropic anger I held. Understanding that these reactions are part of the human condition softened my stance.

The second step was learning to transmute the pain into something less serious, even humorous. I started playing out alternate scenarios in my mind:

- What if we grouped people based on their blood type or hair color the same way we use skin color for race?

- What if we had “tall supremacists” or “blood type O activists”?

The absurdity of these questions helped me see racial grouping as just another one of humanity’s many glitches—a leftover from our evolutionary history.

Managing Our Own Suffering

Rather than see it as an inevitable source of suffering, I learned to treat these moments of racism as reflections of a flawed but predictable aspect of human behavior. My objection to being grouped based on race is rooted in the same desire to be seen as an individual, rather than just a variant of a group. Had I been grouped by any other arbitrary trait—my height, blood type, or ancestry—I would have had the same strong reaction.

This shift in perspective didn’t erase the pain of these experiences, but it helped me put them into context. I was able to see the broader picture and, in turn, reduce the emotional sting they left behind.

Conclusion

I think we can take responsibility for managing our suffering, even in response to pains we judge as unjust. As humans, we have the ability to give meaning to painful experiences by reshaping the context around them. One approach that’s worked for me is learning to re-frame these situations and accept that, while they can’t always be avoided, they don’t have to define how much I suffer.